Dèserts

- Juan Pablo Correa

- 29 ago 2024

- 5 Min. de lectura

Context

This is an analysis of the first part of the work Dèserts, an Amazing piece made by Edgar Vàrese. Composed between 1950 and 1954. After a 10 years period where we didn't listen anything from Varèse. Déserts has been recognized as a master piece of Varèse, in which he achieved the highest point of language mastery.

It is important to mention that initially, Déserts was conceived to be a multimedia piece, Varèse intended to make a film, he even wanted to make contact with Walt Disney for the realization of it.

We could also take a look of what inspired him and what would be the significance of the deserts for him. From 1936 to 1937 Varèse goes to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Period in which he had the opportunity of a philosophic reflection about art and the life itself. (Santa fe is a rather desertic zone). In interviews for the RTF, Varèse mentioned about the meaning of Déserts for him:

"Of all those [deserts] through which man passes or may pass, physical deserts - those of land, sea and sky, of sand and snow, of interstellar spaces and great cities - but also those of his mind, of that distant inner space that no telescope can reach, where man is alone."

The electronic interpolations where possible due to an early donation of Alfred L. Copley, an Ampex 401A tape recorder.

So, the recording of these parts began in 1952 in Philadelphia, with the help of Fred Plaut, they recorded many factories, foundries and sawmilles. Then, they where finished in Paris, with Pierre Schaeffer at his "Club d'essai", one month and a half before the premiere. Which by the way was a big scandal; something similar to the premiere of the Rite of the Spring, mostly because the program was between pieces by Mozart and Tchaikovsky.

Years later, Varèse began to work more on these interpolations until making the final version in 1961.

Analysis

In this analysis I want to go from the ground up to the top of the form. Firstly analyzing the Micro-form to the Meso-form. For the scope of this presentation, in discussion with Jean-Luc Fafchamps, we decided that a way to be effective is to analyze the first section and give an overlook to the rest of the sections.

Micro-form

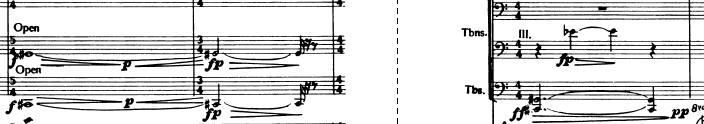

So, this is the paradigmatic analysis, I take a first look at the principal 3 sound objects and then to the 4th one.

One of the most prominent aspects that this analysis shows, is that Varèse was not thinking of motives as we know it; he was thinking of gestures and how he could change them each time he would play it. Furthermore, changing the quality of the object through different resonances. Sometimes an object could be played entirely by a set of instruments keeping the resonance or diverging e.g between the two horn players.

I considered that for these 4 citations, it was better to just copy the entire part without reduction.

Sound Object 1 | Sound Object 2 | Sound Object 3 |

| ||

|

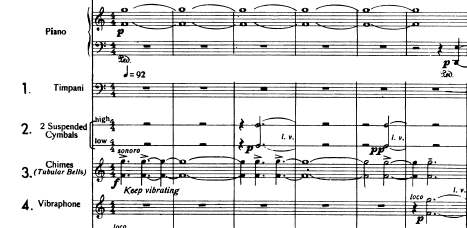

There's a particular passage a the beginning, where the piano is sustaining the first set of notes, but the tubular bells attack them on different times. Supposedly we could listen the piano strings sound by empathy.

Varèse shows us as early that he is searching for the quality in a sound.

At this point I would like to bring up an analysis of the form by Tim Stephenson(1988), in which he describes each section. I agree a lot with this analysis, but I think it could be better to call it movement, because, clearly the material and the focus between these are very different and there are passages inside it that would be better called sections, Anyways, we're gonna stick with his definition for the sake of clarity.

Between the Section 1 and Section 2 I find that there's a debatable overlap. From the mm. 87 to mm. 117 the percussion begins to take a more active part on the music and ceases to use so much pitched percussion, proposing other developments on the theme, which weren't done before the first O.S. This phenomenon stops in mm.117 and continues at mm. 132 where they begin to slowly get prominence until measure 154 where they got a brief solo, and then until mm. 164.

For understanding the relationships between the acoustic and electronic interpolations in Déserts we have to somehow go in a different line than the conventional analysis. As we can see, there was a principle of construction where Vàrese was not thinking about using certain harmony or scale itself but sound masses, sound objects, timbres and frequency changes.

In the own words of Varèse:

As the term “music” seems gradually to have shrunk to mean much less than it should, I prefer to use the expression “organized sound,” and avoid the monotonous question: “But is it music?” “Organized sound” seems better to take in the dual aspect of music as an art-science, with all the recent laboratory discoveries which permit us to hope for the unconditional liberation of music, as well as covering, without dispute, my own music in progress and its requirements.

So we can make asumptions based on studying one of the sections and then compare these principles to get a better understanding of what is the organisation of the interpolations.

One of the most important cases, is in the first section.

We can see this organisation in the first section from the beginning to the measure 22.

And we could make the same analysis with the first interpolation, between 3:40 and 4:05.

It happens again from 5:10 to 5:28

There is something very interesting that happens at the end of the interpolation and shows us that there is an absolute relationship and the music is though coherently. So, from 5:25 of the interpolation (which would correspond to the sound object 1), it gets connected to measure 83 to 92. The instruments use the same pitch as the sampled sound, apparently a metal plate which is mimicked by the brass.

This kind of thing also happens In the second section. We could take a look at mm.199 to 203. A game between pianissimo notes, using the claves, which we could associate to the passage of 14:09 to the end of the 2nd interpolation and that gets connected to to the next part, especially because of the mm. 228 and 231 of the Xylophone.

Between the Interpolation 3 and including the ensemble part, there's not the same approach to give coherence to the interpolation. Rather, we can see a disruption, the phrases are very different between each other. I think that would be the focus in this 3rd part.

Orchestration

Vàrese did not use a classic orchestration, he began to do smaller ensambles since Ecuatorial

According to Wikipedia:

Klangfarbenmelodie (German for "sound-color melody") is a musical technique that involves splitting a musical line or melody between several instruments, rather than assigning it to just one instrument (or set of instruments), thereby adding color (timbre) and texture to the melodic line. The technique is sometimes compared to "pointillism", a neo-impressionist painting technique.

mm.199

mm. 212

References

Lalitte, Philippe. (2010). Déserts d’Edgard Varèse ou l’apothéose du son.

Dallaire, F. (2014). Son organisé, partition sonore, ordre musical : la pensée et la pratique cinématographiques d’Edgard Varèse et de Michel Fano. _Intersections_, _33_(1), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.7202/1025556ar

Edgard VARÈSE, « Organized Sound for the Sound Film », The Commonwealth, vol. 33, n° 8, 13 décembre 1940, p. 204-205.

The musical language of Edgard Varèse. Stephenson, Tim. University of Surrey (United Kingdom) ProQuest Dissertation & Theses, 1988.

Comentarios